On December 20, 2017, in PRB v. Beijing Winsunny Harmony Science & Technology Co., Ltd. ((2016)最高法行再 41 号), the Supreme Court held that a Markush claim, when directed to a class of chemical compounds, should be interpreted as a set of Markush elements rather than a set of independent specific compounds. This case involved a petition for retrial filed by the Patent Reexamination Board of SIPO (“PRB”), requesting the Supreme Court to review the second-instance decision issued by the Beijing High People’s Court (“High Court”). In reversing the PRB’s decision in the invalidation proceedings initiated by Beijing Winsunny Harmony Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (“Winsunny”), the High Court recognized a Markush claim as encompassing a set of parallel technical solutions.

The stark divergence between the PRB and the High Court reflected the longstanding uncertainty and confusion within the Chinese patent community regarding the interpretation of Markush claims. While the Supreme Court’s interpretation may resolve this divergence, it also casts significant doubt over the flexibility to amend Markush claims during prosecution and post-grant invalidation proceedings.

Background

The patent at issue is CN Patent No. 97126347.7 (the “’477 patent”), entitled Method for Preparing a Pharmaceutical Composition for the Treatment or Prevention of Hypertension, issued to Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited (“Daiichi Sankyo”) on September 24, 2003.

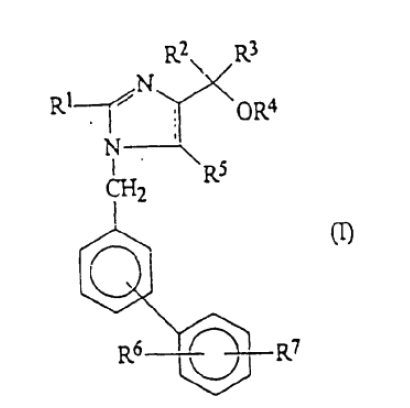

The ’477 patent formally contains only a single claim directed to a method for preparing a pharmaceutical composition for the treatment or prevention of hypertension, comprising mixing an anti-hypertension agent with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier or diluent. The anti-hypertension agent is defined as at least one compound of formula (I), or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or ester thereof, in which each of R1–R7 is independently selected from a list of alternative substituents. It is clear that the claim is a Markush-type claim, relating to a Markush compound of formula (I).

Earlier Proceedings

On April 23, 2010, Winsunny filed a request for invalidation with the PRB against the ’477 patent, citing lack of inventiveness, insufficient support in the description, and lack of clarity.

In response, Daiichi Sankyo amended the claim by:

- Deleting “or ester” from the phrase “or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or ester thereof” to address the issues of insufficient support and lack of clarity; and

- Removing certain alternatives from the lists for R4 and R5 in an effort to establish inventiveness over the prior art.

The PRB then held an oral hearing to examine the admissibility of these amendments. It found the deletion of “or ester” acceptable but deemed the deletion of alternatives for R4 and R5 inadmissible, as it did not fall within the permissible forms of amendment in invalidation proceedings. Both Daiichi Sankyo and Winsunny accepted the PRB’s findings, and Daiichi Sankyo resubmitted the amended claim accordingly. Based on the resubmitted amendment, the PRB ruled that the patent remains valid.

Winsunny appealed the invalidation decision to the Beijing First Intermediate People’s Court (“Intermediate Court”), arguing, among other things, that the PRB misapplied the law in rejecting the deletion of alternatives from the Markush compound. However, the Intermediate Court upheld the PRB’s decision, affirming that such deletions are inadmissible. The court specifically noted that while deletion of a technical solution is generally permissible, deletion of Markush elements from a Markush claim is not equivalent to removing one or more parallel technical solutions.

High Court’s Decision

Winsunny then appealed to the High Court, which overturned both the PRB’s decision and the Intermediate Court’s ruling. The High Court disagreed with the PRB’s interpretation of a Markush claim, holding that it is a special claim format comprising multiple variables, each defined by a list of parallel options. A Markush compound, it stated, should be regarded as a set of chemical compounds in parallel, each representing an independent technical solution. Since a Markush claim is merely a format for claiming a set of “parallel” technical solutions, deletion of certain Markush elements corresponds to deletion of technical solutions, which should be permissible during prosecution and invalidation proceedings. The only limitation is that such amendments must not result in a specific compound that is not explicitly disclosed in the description.

The High Court inferred from the PRB and Intermediate Court’s refusal to allow deletion of Markush elements that they view a Markush claim as a “monolithic” technical solution. It further expressed concern that overly strict limitations on permissible amendments could undermine the viability of Markush claims. The court even warned that if deletion of Markush elements is not allowed to overcome prior art, such claims may become highly vulnerable or even meaningless.

The PRB petitioned the Supreme Court for retrial, arguing that the High Court erred in interpreting a Markush structure as a set of independent specific compounds and in treating deletion of Markush elements as removal of parallel technical solutions. The PRB maintained that a Markush structure represented a “monolithic” generalized technical solution, even though each variable is defined by a list of discrete parallel options. It contended that deletion of Markush elements should be viewed as narrowing a variable to reduce the claim scope, rather than removing parallel technical solutions. If the narrowed variable resulting from such deletion lacks a clear basis in the original description and claims, the new claim should be rejected as exceeding the scope of the application as filed.

The Supreme Court agreed with the PRB and overturns the High Court’s judgment. It held that a Markush claim should be interpreted as a monolithic claim defining multiple parallel options within a single variable, rather than a set of parallel technical solutions. The Court emphasized that allowing patentees to arbitrarily delete Markush elements introduces uncertainty into the scope of a Markush claim, which is contrary to the public interest.

Looking Forward

The Supreme Court’s decision provides a definitive answer to the question of how a Markush claim should be interpreted: either as a monolithic technical solution featuring a plurality of parallel options defined by one or more variables, or as a set of parallel technical solutions that can be individually separated for each option. Although these two interpretations may result in substantially the same claim breadth, they lead to significantly different outcomes regarding the admissibility of amendments to the claim.

SIPO is known for its strict standards on the admissibility of amendments to claims and descriptions during both prosecution and invalidation proceedings. Under the Patent Law, amendments must not exceed the scope of disclosure contained in the original description and claims. In practice, SIPO interprets this “scope of disclosure” narrowly, requiring that any amendment be “directly and unambiguously” derivable from the original application. In many cases, examiners equate this standard with literal disclosure. For example, an amendment that narrows a claim by replacing a “genus” feature with a “subgenus” will be deemed unacceptable if the narrowed claim cannot be directly and unambiguously derived from the original application by a person skilled in the art – even if the original application discloses sufficient “species” to support the newly introduced “subgenus.”

In invalidation proceedings, the scope of permissible amendments is even more limited. Acceptable amendments include only:

- deletion of a claim;

- deletion of a technical solution;

- addition of one or more technical features from other claims to further define a claim; and

- correction of obvious errors.

This context helps explain the PRB’s rationale for rejecting amendments to a Markush claim by deleting Markush elements. A variable (or Markush group) in a Markush claim is treated as an “artificial” genus encompassing a list of species or Markush elements. Deleting any element effectively creates a new “subgenus” with a reduced list of elements. Such a narrowed claim is considered to exceed the scope of disclosure in the original application and is therefore inadmissible.

Markush claims have long been regarded as a powerful tool for claiming broad protection, particularly in chemical compound-related inventions, while avoiding prior art. However, the Supreme Court’s decision—disallowing amendments to Markush claims by deleting elements to overcome prior art—makes such claims significantly more vulnerable to patentability challenges, both during prosecution and in invalidation proceedings. The High Court even warned that Markush claims could become meaningless if deletion of elements is not permitted to avoid prior art.

Going forward, patent owners asserting Markush claims must carefully assess the strength of their claims, especially in scenarios where one Markush element may be deemed problematic, yet cannot be removed. For claim drafters, it is now more important than ever to thoughtfully structure claims at the outset. For example, it is advisable to include sufficient dependent claims derived from an independent Markush claim to serve as fallback positions for potential amendments. One must abandon the illusion that a single Markush independent claim inherently covers hundreds or thousands of separable and arbitrarily removable technical solutions.